Ninety percent of the excess heat accumulated on Earth ends up in the world's oceans. "Every day, what we experience as major changes in the atmosphere actually represents only 1% of climate change," says oceanographer Jean-Baptiste Sallée. To understand the extent of global warming, we must go below the surface of the ocean and in particular the Southern Ocean. This is the objective of the SO-CHIC project.

Initiated in 2019 by Sorbonne University's Oceanography and Climate Laboratory, the SO-CHIC (Southern Ocean Carbon and Heat Impact on Climate) project brings together 16 international institutional partners and some 50 specialists in physics, oceanography, climatology and biogeochemistry. Funded by the European Commission to the tune of eight million euros for a period of five years, the goal is to understand the processes that control exchanges between the atmosphere, the ocean and the sea ice in the Southern Ocean in order to help reduce the uncertainties associated with forecasting climate change.

The heart of the ocean

Only a few places on Earth connect the ocean surface and the abyss zone, making it possible to absorb heat and carbon from the atmosphere at depth. "This phenomenon is most effective in the Southern Ocean because of the physical and biogeochemical processes that take place there and that are linked to the extreme climatic conditions of this region of the globe," explains Jean-Baptiste Sallée.

The Southern Ocean acts as a real sponge, absorbing three quarters of the heat and carbon from the atmosphere captured by the oceans as a whole, and burying it in the ocean floor. It is also one of the fastest warming oceans on Earth. Its warmer waters are becoming more acidic and losing oxygen. And because they are taking place near the Antarctic ice cap, these changes have a very strong impact on global sea levels. "A very small change in the efficiency of this sponge has major consequences on atmospheric warming," insists the oceanographer. The question lies therefore in knowing how much longer the Southern Ocean will be able to play this role of regulating the global climate as effectively as it does today.

The acceleration of climate change

To understand the extent to which this ocean is changing, scientists have used data collected over the past 25 years by the Astrolabe, an icebreaker that sails between Australia and Antarctica to supply French bases with information. "We have seen that the temperature changes were very significant compared to the natural variability of the Southern Ocean, especially the more fundamental ones that occur in the deep," says Sallée.

One of the next steps in the project is to determine whether this huge amount of heat growing in the deep Southern Ocean will seep into the Antarctic continental shelves and come into contact with the polar cap. "This is one of the major uncertainties about future sea levels. We think that this is likely to be the case, but we can't quantify it yet," warns Jean-Baptiste Sallée.

... due to less oceanic absorption of heat and carbon

By analyzing the ocean's global physical dataset over the past 50 years, SO-CHIC scientists have good reason to believe that climate change will make it even more difficult for the ocean to absorb carbon and heat. "We can see very clearly that at the global level, the ocean is decoupling between the surface layer and the abyss. This is because the temperature and density of the ocean surface is changing much faster than in the deep ocean. It's exactly like adding a layer of oil on top of water; the mixing between the different layers of the ocean doesn't happen as well." The team also demonstrated, in a paper published in Nature in 2021, that this phenomenon of decoupling between the surface and the depths took place seven times faster than existing models suggested.

December 2021: the first SO-CHIC observation campaign

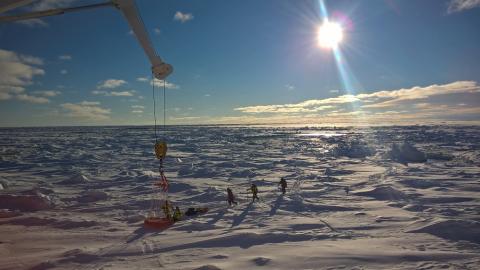

The research team is also interested in more abrupt changes that take place in the ocean, such as the establishment of a chimney between the abyss and the atmosphere. This relatively rare phenomenon releases an enormous amount of heat, creating holes in the ice pack the size of half of France. To understand these processes, scientists will leave in December to install instruments on an underwater mountain. "We are going to deploy autonomous instruments, adapted to extreme conditions and piloted remotely, and leave them for a year under the southern ice pack," explains the oceanographer.

Campagne en Antarctique ©Jean-Baptiste Sallée

To prepare this first observation campaign, researchers rely on modeling work. "We have created a high-resolution model of the area to represent these small-scale processes that are not represented in current climate models," explains Jean-Baptiste Sallée. "Thanks to this digital representation, we can conduct virtual experiments and know precisely what type of sampling we need, which instruments to use, where to deploy them, and how to pilot them, for example."

Other campaigns led by international partners, such as the one conducted last year by the German Polar Institute, also help to collect valuable observations that are used in the project.

SO-CHIC's research feeds directly into the reports of the IPCC, the intergovernmental panel on climate change to which Jean-Baptiste Sallée belongs and which is at the heart of international climate negotiations. "Our work is notably cited in the sixth assessment of the report published in 2021," says the researcher. The project team will also participate this year in the COP26 during an event on polar climate change that will take place on the European Commission's pavilion in Glasgow.